Toyota may have pioneered the just-in-time production strategy, but when it comes to chips, its decision to stock key components for cars dates back a decade to the Fukushima disaster.

After the disaster cut Toyota’s supply chains on March 11, 2011, the world’s largest automaker realized that the turnaround time for semiconductors was far too long to withstand devastating shocks such as natural disasters.

That’s why Toyota came up with a business continuity plan (BCP) that requires suppliers to stock anywhere from two to six months worth of chips for the Japanese carmaker, depending on the time it takes from order to delivery, according to four sources.

And that’s why Toyota has so far been largely unharmed by a global semiconductor shortage following a surge in demand for electrical goods under coronavirus locks that have forced many rival automakers to suspend production, the sources said.

Toyota has increased its vehicle production for the fiscal year ending this month and increased its forecasted profit for the full year by 54%.

“Toyota was, as far as we can tell, the only automaker well-equipped to deal with chip shortages,” said a person familiar with Harman International, which specializes in car stereo systems, displays and driver assistance systems.

Two of the sources who spoke to Reuters are Toyota engineers, and the others are from companies involved in the chip business.

Toyota surprised rivals and investors last month when it said its production would not be significantly disrupted by chip shortages, even as Volkswagen, General Motors, Ford, Honda and Stellantis, among others, have been forced to slow down or shut down some of its production. aprons.

Toyota, meanwhile, has increased its vehicle production for the fiscal year ending this month and increased its forecast full-year profit by 54%.

Classic slim solution

The source Harman knew said the company, which is part of Samsung Electronics in South Korea, suffered a shortage of central processing units (CPUs) and integrated circuits for power management as early as November last year.

While Harman doesn’t make chips, its continuity agreement with Toyota required it to prioritize the automaker and ensure it had enough semiconductors to maintain supplies for its digital systems for four months or more, the source said.

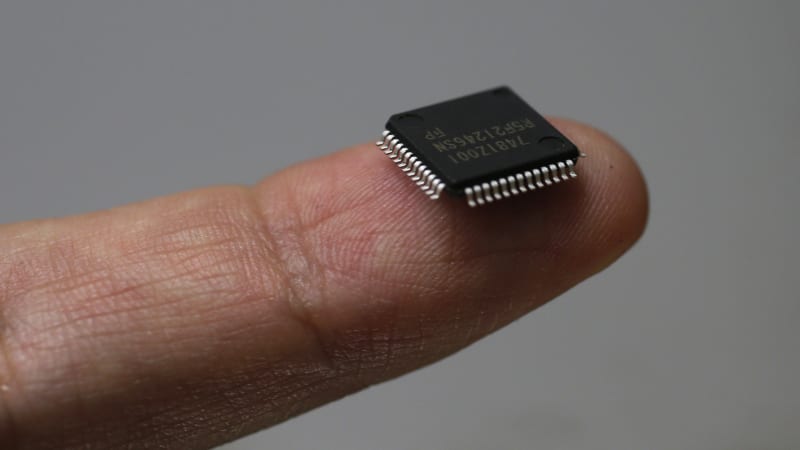

The chips that are particularly scarce now are microcontroller units (MCUs) that control a range of functions such as braking, acceleration, steering, ignition, combustion, tire pressure gauges and rain sensors, the four sources told Reuters.

Toyota estimated that 1,200 parts and materials could be compromised in the aftermath of the earthquake and drew up a list of 500 priority items that needed safe delivery.

However, Toyota changed the way it buys MCUs and other microchips after the 2011 earthquake, which triggered a tsunami that killed more than 22,000 people and caused a deadly meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, Toyota estimated that the procurement of more than 1,200 parts and materials could be affected and drew up a list of 500 priority items that would require safe delivery in the future, including semiconductors made by the major Japanese chip supplier Renesas Electronics.

The consequences of the disaster were so severe that it took Toyota six months to return production outside Japan to normal levels, having done so at home two months earlier.

It was a major shock to Toyota’s just-in-time system, as a smooth flow of components from suppliers to factories to assembly lines – as well as streamlined inventories – was central to its emergence as a leader in efficiency and quality.

At a time when supply chain risk is now central to almost every industry, this move shows how Toyota was ready to throw out its own semiconductor rulebook – and reap the benefits.

A Toyota spokesperson said one of the goals of its lean inventories strategy was to become sensitive to inefficiencies and risk in supply chains, identify the potentially most damaging bottlenecks and figure out how to avoid them.

“The BCP was a classic streamlined solution for us,” he said.

No black boxes

Toyota pays for its inventory deals with chip suppliers by repaying some of the cost savings it demands from them every year during the life cycle of each car model under so-called annual cost-cutting programs, the sources said.

Inventories of MCU chips – which often combine multiple technologies, CPUs, flash memory, and other devices – are maintained for Toyota by component suppliers such as Denso, which is partially owned by Toyota Group, chip makers such as Renesas and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing, and chip dealers . .

While there are several types of MCUs, those short on now are not advanced chips, but more common chips with semiconductor nodes ranging from 28 to 40 nanometers, the sources said.

Toyota has another advantage through its long-standing policy of making sure it understands all the technology used in its cars, rather than relying on suppliers to provide “black boxes”.

Toyota’s chips continuity plans have also offset the impact of natural disasters exacerbated by climate change, such as more severe typhoons and rainstorms that often cause floods and landslides across Japan, including the southern Kyushu region manufacturing hub where Renesas also makes chips.

One of the sources involved in semiconductor supply said that Toyota and its subsidiaries had become “extra risk-averse and sensitive” to the effects of climate change. But natural disasters and the climate aren’t the only threats on the horizon.

Automakers fear there will be more disruptions in chip supply as a result of rising demand as cars become more digital and electric, as well as the fierce rivalry for chips from makers of smartphones to computers and airplanes to industrial robots.

The sources said Toyota has another advantage over some rivals when it comes to chips, thanks to its years of policy of making sure it understands all the technology used in its cars, rather than relying on suppliers to “black out”. boxes “.

“This basic approach sets us apart,” said one of the sources, a Toyota engineer.

“From what causes semiconductor errors to gory details about manufacturing processes, such as what gases and chemicals you use to make the process work, we understand the technology inside out. “just buy those technologies. “

“Losing our grip?”

The use of semiconductors and digital technologies by car manufacturers has exploded this century with the emergence of hybrid and fully electric vehicles, autonomous driving and connected car features.

Those innovations require even more computing power and, in part, utilize a new category of semiconductors called system on a chip, or SoC, that roughly combines multiple CPUs on one logic board.

The technology is so new and specialized that many car manufacturers have left it to major parts suppliers to manage the risks.

However, in keeping with its ‘no black box’ approach, Toyota developed an in-depth internal understanding of semiconductors in preparation for the launch of its successful Prius hybrid in 1997.

“We were fine this time, but who knows what’s in store for us in the future?”

Years before, it took engineering talent from the chip industry and opened a semiconductor plant in 1989 to help design and manufacture MCUs used to drive Prius powertrain systems.

Toyota designed and manufactured its own MCUs and other chips for three decades until it handed over its chip factory to Denso in 2019 to consolidate the vendor’s business.

The four sources said Toyota’s early drive to develop an in-depth understanding of semiconductor design and manufacturing processes was a major reason why, in addition to continuity contracts, it managed to avoid being hit by the shortages.

However, two of the sources said they were concerned that the deal with Denso might indicate that Toyota was finally ready to forgo the no black box approach, even though the supplier is part of the wider Toyota Group.

“We were fine this time, but who knows what’s in store for us in the future?” a source said. “Maybe we are losing our grip on technology in the name of the efficiency of technological development.”