As you know, microchips can be found in just about everything from the obvious (cell phones, smart devices) to the not so obvious (e.g., your power tool’s lithium-ion battery). Inside your car are computer modules that control almost everything from engine and transmission operation to in-car technology and virtually everything in between. Long gone are the days when cars had “a” computer. Today they are everywhere and interconnected in a way that makes them all essential to the fundamental functioning of a car.

The microchip is as ubiquitous in modern consumer products as wood is in residential construction. But unlike wood, microchips are not just a refined raw material. While many chips (such as those used for computer memory) have numerous uses, that does not mean that all computer chips are created equal. The specialized computers that manage the powertrain components, infotainment and safety systems on board your car cannot simply be replaced by what’s available.

Semiconductor manufacturing is a complex and expensive process, limiting the size of the field, and not every manufacturer is able to provide the chips that car manufacturers need. In general, silicon makers are steps away from assembling the products that power their chips, but some, like Intel, Samsung, and even Foxconn, are household names on the frontier.

Others, like Renesas and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), are silent behemoths, best known to industry insiders and tech enthusiasts. While companies like Intel manufacture many of their own chips, they and others, including computer giants AMD and Nvidia, often rely on contract manufacturers such as TSMC to produce chips.

The production of (and demand for) chips is greater than ever, so why are we all of a sudden? The short answer is, predictably, “COVID” or, more generally, “market forces”. Do you want the long answer? Just do it. It’s a bumpy road.

The origin of COVID

For starters, early stage silicon wafer and microchip production was hit by COVID, just like any other industry. The impact of this was negligible as it happened while the demand for cars was similarly suppressed. Dealers closed their doors to incoming customers and the lines went inactive to minimize the first wave of coronavirus infections. When production reopened, automakers remained cautious with their supply orders as demand slowly recovered amid uncertain economic conditions, widespread unemployment and ongoing health problems.

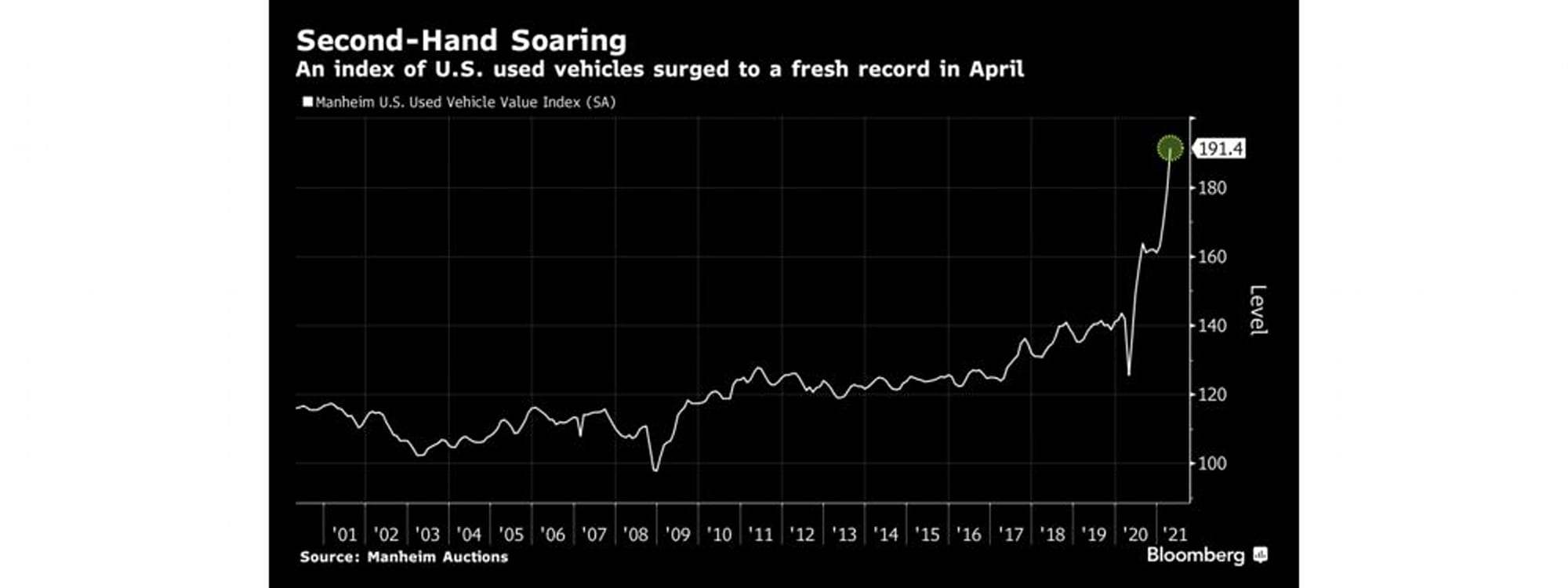

The lack of dealer traffic also had an additional consequence: since customers did not buy new cars, they also did not trade old ones, putting pressure on businesses that depended on used inventory, including the new generation of Internet cars. based car dealers such as Carvana and Vroom. This was the start of the rise in used car values, but we’ll get to that later.

At home in the meantime …

As COVID-related social and workplace restrictions began to apply, the demand for cars may have fallen, but the demand for consumer electronics has skyrocketed. Computers, video game consoles, and other personal productivity and entertainment devices quickly gained popularity as consumers discovered that their existing hardware was not up to the new normal. Enterprise demand also increased as companies around the world rushed to equip their workforce for remote operations.

Like everything else in the modern industrial supply chain, microchips are produced on the basis of demand, and as the demand for the automotive industry declines and the demand for consumer electronics rises, chip makers have adapted their production schedules accordingly. To further exacerbate the situation, the second half of 2020 also saw the launch of the latest generation of video game consoles from both Microsoft and Sony, along with a new generation of desktop and mobile GPUs and CPUs from Nvidia, AMD and Intel. All of these launches competed for the same slice of the consumer silicon pie.

To make matters worse, growth in the consumer electronics and ship-to-home sectors added even more demand. From the data centers that power large logistics operations to the forklift trucks that move products through warehouses, everything relies on microchips. Those same chip manufacturers foundries that produce microchips? Yes, they are often managed by the computers that produce them.

As this wave of consumer demand intensified in the fall, circumstances conspired to drive up demand for new cars. Now that restrictions were lifted and the economy returned to normal, shoppers returned. Starved for volume, dealers and manufacturers welcomed their customers with open arms – and open cash boxes – and offered deals to draw shoppers to the showrooms. It worked, and when the fourth quarter of 2020 ended, it was better for the auto industry, even though alarm bells started ringing in the background.

A perfect storm

The first signs of the emerging deficit were in the still strongly growing consumer sector. Even as automotive demand was just growing, the silicon supply was already thin on the ground; just ask any holiday buyer looking for a PlayStation 5 or Xbox Series X. Some automakers said they were anticipating a chip shortage as early as December.

But even when chip makers shifted production to automotive supply channels, they simply weren’t able to ramp up production enough to meet the revived (and rising) demand. The ongoing shortage of used car inventory exacerbated the situation. As the prices of second-hand models rose, they eased the downward pressure on new car prices. Incentives started to dry up when customers chose to buy new instead of overpaying (in their eyes) for someone else’s leftovers.

Then 2021 brought even more complications. In March, Renesas, one of the largest automotive chip suppliers, was hit by a massive fire that halted chip production and damaged most of its equipment to the point that it could no longer be used. Renesas restarted production in mid-April, but does not expect to be back to full capacity until the third quarter. Microchip production can take up to two months to final assembly, meaning it could be August or September before Renesas’ supply reaches all of its end customers in normal quantities, allowing vehicle production to resume.

Effects

Since the beginning of the year, just about every major carmaker has been forced to shut down production of at least one vehicle, and in many cases, the shutdowns affect high volume and high margin offers like the Ford F-150. Depending on the specific chips that OEMs are struggling with, some have found ways to keep the lines running by just building cars without certain options, such as advanced safety and driver assistance systems. In many cases, however, the missing chips are critical, bringing assembly lines to a standstill until they can be purchased.

Otherwise, explosive first-quarter sales results were limited in many cases by the inability to produce components for highly popular models. We mentioned the Ford F Series above, but similar issues have plagued shoppers looking for some versions of Toyota’s RAV4 and both Honda’s Accord and Civic models, among many, many others. Honda and Nissan said the chip crisis could cost up to 250,000 sales. According to a forecast, the number of “lost cars”, that is, cars that will not be built due to the shortage of chips, is 2.5 million vehicles.

To make matters worse, this all comes to a head during the tax season, which is typically a busy time of year for auto dealers. Americans often convert their tax refunds into down payments on new cars and trucks. Extra pressure this year comes in the form of COVID relief, giving shoppers even more cash-flush. The rest is basic demand and supply; the former is scarce and the latter is currently unsatisfactory.

And while the shortage of chips is not directly responsible for the current situation in the used car market, as we illustrated above, the two go hand in hand. The end result is that the prices of both new and used cars are shockingly high. There has not been a better time in recent history to sell an unnecessary car; unfortunately, there hasn’t been a worse time to buy one either.

Outlook

TSMC hopes to meet the minimum requirements of its customers by the end of June, but even if microchip production as a whole can meet manufacturing requirements by the end of 2021, it will likely take longer for the market to normalize. The shortage of used cars will remain an issue as long as new car inventory growth remains stunted as shoppers will not have new purchases that they would normally trade in their new cars for. That means high prices on both ends of the spectrum.

And while governments and industry lobbies may be trying to pressure semiconductor manufacturers to increase production, it’s not as easy as just cranking up the pit. As with other specialty industries, the tooling involved is complex and expensive. In the longer term, investors want to expand microchip production in the US. Intel already produces silicon in the American Southwest, and startups hoping to do the same elsewhere in the US have caught the attention of investors.